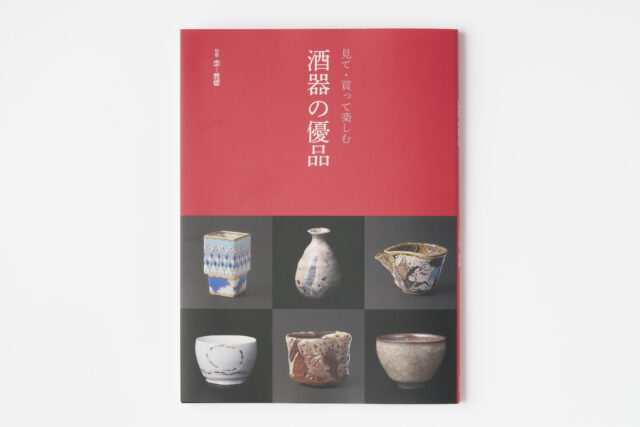

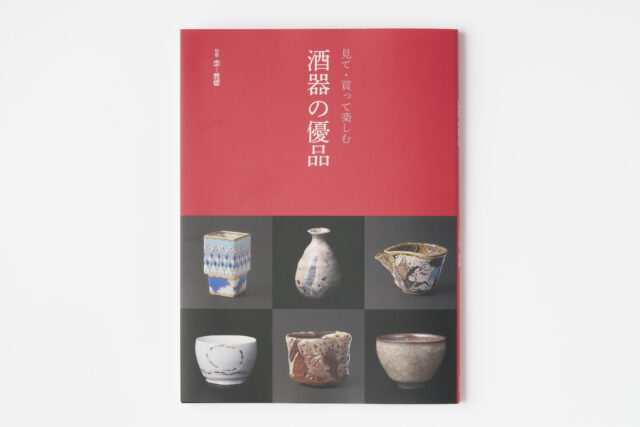

The Publication of “Discover, Acquire, Enjoy – The Excellent Sake Ware”: A Special Issue of the Quarterly Journal “Honoho Geijutsu” or “The Art of Fire”

KOGEI Topics VOL.26

VOL.1-26

Update

VOL.1-52

Update

VOL.1-4

Update

VOL.1-23

Update

VOL.1-27

Update

VOL.1-4

Update

VOL.1-3

Update

VOL.1

Update

VOL.1-7

Update

VOL.1-32

Update

VOL.1-12

Update

VOL.1

Update

We share a variety of information and perspectives on Japanese crafts, including exhibition information and interviews.

KOGEI Topics VOL.26

Featured Exhibitions & Events VOL.52

Editor's Column “The Path of Japanese Crafts” Part2: Modern Society and Kogei VOL.4

Featured Exhibitions & Events VOL.51

Jan 6 – Mar 10, 2026

The Japan Folk Crafts Museum

Jan 31 – Mar 15, 2026

Museum of Modern Ceramic Art, Gifu

Feb 7 – May 24, 2026

TOYOTA CITY FOLK CRAFT MUSEUM

Feb 14 – Mar 15, 2026

Fukui Fine Arts Museum

When considering luxury from a historical perspective, it is impossible to overlook the presence of Western aristocratic culture. In medieval Europe, the nobility held considerable power under the feudal system, purchasing goods far beyond what was necessary for daily life and enjoying an elegant and extravagant lifestyle. Their opulent way of living, depicted in numerous paintings and other artworks, continues to shape the fundamental impression many people have of the word “luxury” even today.

In Japan as well, aristocratic culture flourished during the Heian period (794-1185), yet unlike in the West, it did not continue for many centuries. Throughout Japanese history, there were certainly people of wealth who lived in splendor. However, within a society that valued the group over the individual and found meaning in a spirit of simplicity and a modest way of living, even those who enjoyed luxurious lives were expected to maintain a certain modest posture. This is where the complexity of interpreting luxury in the Japanese context arises.

Furthermore, the meaning of what is considered luxurious changes with the times. In this sense, luxury is very similar to beauty. Our perspective on beauty shifts depending on the era and the culture. In painting, there were periods when the Impressionists were admired, and others when realism flourished. Fashion, too, takes on different characteristics in each time and cultural setting. Luxury follows a similar pattern. While gold and gemstones have long been regarded as valuable, there are items such as the so-called “three sacred household appliances” of postwar Japan, namely televisions, washing machines and refrigerators, that were once considered symbols of luxury but have since become commonplace and can no longer be described as luxurious. In the world of the tea ceremony, even humble everyday wares can be used as tea utensils, creating a new kind of aesthetic. As the sharing economy continues to grow and the very idea of value in ownership evolves, we may eventually reach a time when purchasing expensive objects is no longer seen as an expression of luxury.

In today’s society, where material abundance has become the norm, luxury is increasingly understood not as something material but as an experience or a moment. Travel is one such experience. Even today, it is regarded as a form of luxury, perhaps because it still requires effort to move oneself across distances. A good journey demands either time or money, or in many cases, both. The reason travel is considered luxurious is not simply because it takes one far away. It is because many people feel that what they gain from a journey in which they invest time and resources becomes a treasure in their lives.

From this perspective, contemporary luxury seems closely connected to the idea of ikigai, a Japanese notion of purpose that grows gradually through time and relationships. Unlike a hobby, ikigai emerges through time, within relationships with others, as one creates some form of value. It is not something that can be attained quickly. When we look more deeply at the concept of luxury, we may find that it too points toward a richness that unfolds gradually over time.

If one were to take a slightly critical view, luxury can be understood as something inherently relative, always measured in comparison with others. There is a standard, and luxury exists only when one surpasses that standard. In a communal setting where everyone eats the same food, wears the same clothing and performs the same work, the feeling of luxury would hardly arise. Luxury is a sensibility that emerged from hierarchical societies, and it cannot be separated from human desire. This is something we need to acknowledge.

Still, this does not mean that one should abandon desire entirely and live only in a state of simplicity, wasting nothing. It is precisely because humans have desires that they continue to look toward the future and evolve of their own accord. The presence of desire, tempered by reason, is what makes us human. If everyone were to live modestly without desire, we would lose sight of hope for the future. In the era ahead, the act of contemplating and pursuing what true luxury means should not be seen as greed. Rather, it is important to recognize that such longing can become a source of strength that guides the way we live.

“Wealth consists not in having great possessions, but in having few wants.”

These are the words of the ancient Greek philosopher Epictetus. It is undeniable that the meaning of luxury up to now has been tied to an idea of abundance defined through comparison with others. This is precisely why it is important to continue questioning the essence of richness itself. In this context, the Japanese cultural appreciation for creating and valuing yohaku, or intentional empty space, may offer new insight into how we might think about luxury in the future.

There is a saying in Japan that the secret to longevity is to stop eating when one feels eighty percent full. If we were to apply this idea inversely to luxury, we might describe it as the “luxury of leaving room,” a mindset that could be seen as deeply Japanese. The term “quiet luxury,” which has gained attention internationally in recent years, reflects something similar. A sense of richness should be understood not as a result but as something found in the process itself. Time and space hold forms of richness, and of course, so does the human heart. What, then, can be considered rich even when something is missing? What becomes beautiful and precious precisely because it is incomplete? If Japanese culture and kogei or handcrafted objects have a role to play on the international stage, it may lie within these very questions.

If the ultimate point of luxury is to indulge in every possible way, then what, we might ask, lies beyond that? Imagine the following. One achieves success at work and purchases a grand residence. One surrounds oneself with expensive possessions and travels with family on a private jet for vacations. Yet even such a life of abundance, when lived continuously, can leave a lingering sense of emptiness. And perhaps, at the very moment when that feeling begins to surface, something shifts. While walking the dog through the neighborhood, one stops by a small cafe, where a freshly baked piece of bread and a cup of coffee prompt a quiet reconsideration of what richness in life truly means. It is not difficult to imagine a story like this.

What has attracted global attention as wabi-sabi also emerged as an aesthetic and a way of thinking precisely because a world of opulence existed nearby as its contrast. Today, many of us own a smartphone, live in temperature-controlled homes and enjoy access to plentiful means of transportation that allow us to travel freely. This may not be the life of an aristocrat, but compared with the daily lives of ordinary people in the past, it is undeniably comfortable and elegant. What lies on the other side of having everything? What we should be seeking in our time is a new form of luxury, and within it we may find the true richness that gives meaning to our lives.

References

Anzai, Hiroyuki and Kaori Nakano. Decameron About New Luxury: The Quest of Alternative Economy and Culture. (CROSSMEDIA Publishing)

Hickel, Jason. Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. (Toyo Keizai Inc.)